An Egyptian rice farmer shows his drought damaged rice crop in a village near Balqis on June 14, 2008. REUTERS/Nasser Nuri

An Egyptian rice farmer shows his drought damaged rice crop in a village near Balqis on June 14, 2008. REUTERS/Nasser Nuri

LONDON (AlertNet) – For African farmers struggling to cope with increasingly erratic conditions linked to climate change, there’s good – and bad – news.

The good news is that in parts of sub-Saharan Africa, scientists can now issue reasonably reliable seasonal climate forecasts a month or more in advance of the planting season, giving growers a chance to opt for different kinds of crops or other measures to adapt to upcoming conditions.

That has the potential to improve food security in many climate-vulnerable parts of Africa, and reduce the impact on some of the world’s poorest people of droughts, floods and temperature surges.

The bad news is that those forecasts, and other historical weather information farmers need to judge risk and make good decisions, still are not reaching most growers, in part because meteorological data in many African countries is available only at a cost.

Weather information “is an essential resource for adaptation (to climate change) and development,” said James W. Hansen, a researcher on climate change, agriculture and food security at the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) and lead author of a new report on seasonal climate forecasting and agriculture in Africa.

But “as long as these (data) are seen as a revenue source for Met services rather than as a public good for development, the people who are most affected by climate change, climate variability and poverty won’t have much access to innovations,” he said in a telephone interview.

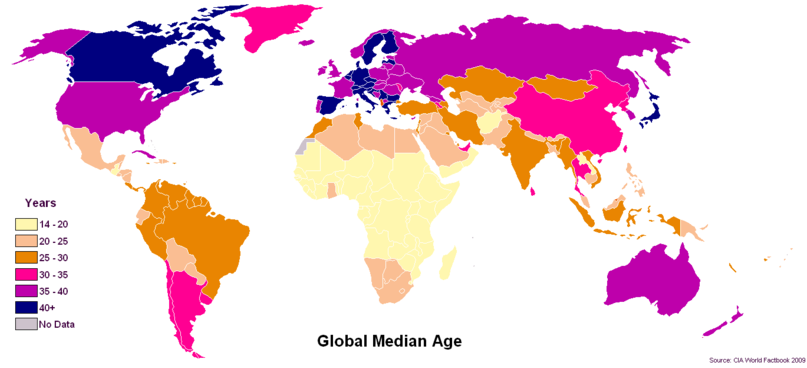

Growing climate variability is making life increasingly difficult for farmers throughout sub-Saharan Africa. Some areas, particularly in southern and eastern Africa, are seeing extended droughts and high temperatures that can make growing staples like maize a challenge. Other regions, including parts of West Africa, have struggled with extreme rainfall.

Altogether “dependence on uncertain rainfall and exposure to climate risk characterize the livelihoods of roughly 70 percent of (sub-Saharan Africa’s) population,” notes the study, published in the journal Experimental Agriculture in March.

SOME PREDICTABLE REGIONS

But scientists are getting increasingly good at predicting seasonal climate conditions in advance, largely because of growing understanding of how Pacific Ocean temperatures – linked to weather phenomena like El Nino and La Nina – influence rainfall in sub-Saharan Africa.

While it is still very difficult to predict seasonal conditions in some parts of Africa – including across the Sahara and the northern parts of the Sahel – other areas are showing potential for predictability, at least in some seasons. They include much of southern Africa up to southern Zambia; a swath of East Africa centered on Kenya; a wide band of West Africa reaching from the Atlantic coast across to Sudan; and a stretch of west-central Africa from the Atlantic coast into the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Already, “skillful forecasts can be produced more than a month before the normal start of the growing season for the short rains in eastern Africa and the main rainy season in southern Africa,” the study noted.

Just as important, the regional forecasts can be “downscaled” to provide more specific local forecasts with only “modest” loss of accuracy, the study said.

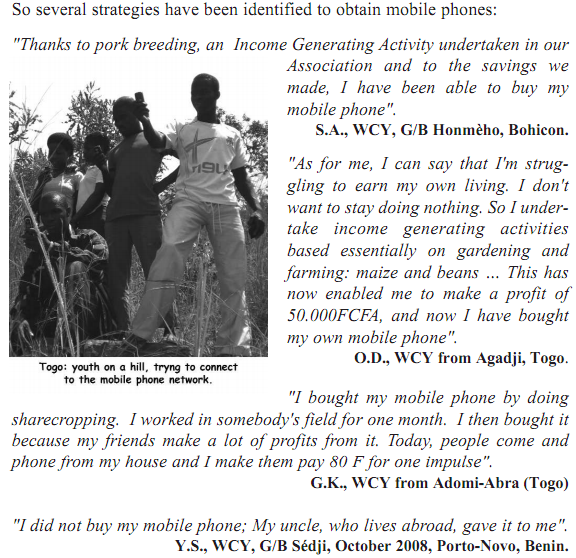

So why aren’t seasonal forecasts yet reaching farmers, particularly given that studies show most are eager to get and act on the information?

Largely it’s the result of communication failures, Hansen said. Meteorologists in many regions tend to oversimplify forecasts, telling farmers there will be higher rainfall, for instance, rather than a 60 percent chance of higher than normal rainfall.

That has led to a lack of trust, particularly when oversimplified predictions don’t come true.

“If I were a smallholder farmer and a climate scientists said it would be more or less rainy, I’d be extremely skeptical. A lot would depend on how much I trust that person,” Hansen noted.

The reality is “farmers understand probability very well. Their lives depend on it,” he said. Leaving the probabilities off forecasts undermines trust and reliability, he said.

But perhaps the most severe problem, he said, is that many African meteorological services see weather data as something to be sold to paying clients – airports, insurance firms, development organizations – rather than released as a public good.

That view is in part the result of structural reforms driven by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, aimed at reducing the hand of governments – often seen as corrupt or inefficient – in services including meteorology, Hansen said. The reforms left many meteorological services dependent on commercial sales of data for funding, he said, a model that is providing difficult to change.

CHANGING THE FUNDING MODEL

Still, efforts are underway. An initiative in Kenya called WIND – Weather Information for Development – aims to help Kenya’s meteorological service find new sources of revenue and make better decisions about what data should be commercialized and what made publicly available free.

In other countries, researchers hope to tempt government meteorological services into releasing satellite data free in exchange for access to information from ground weather stations runs by research organizations.

“If we can get one or two (countries) to break out, and they get new visibility and funding, maybe there can be a domino effect,” Hansen said.

Better seasonal climate forecasts won’t help ease surging food prices around the world, because the surges are driven by rising demand, the scientist warned.

But in some of the poorest parts of the world, good seasonal climate forecasts have the potential to help curb hunger, protect incomes and get some of the world’s most climate-vulnerable people through bad years.

“The ability to anticipate climate fluctuations and their impact on agriculture months in advance should, in principle, enable… opportunities to manage risk,” the study noted.