In recent years there has been explosive growth in the global subscription rate for mobile services. However, estimates are that there remains a gap in coverage somewhere on the order of 1.0-1.5 billion potential subscribers. There is likely in addition to a gap of another 1.0+billion that have coverage but is not affordable Of these, the overwhelming proportion live in rural communities. Several reasons account for this lack of connectivity;

- Economics—for the carriers, there is relatively low revenue compared to cost of delivery,

- Lower hanging fruit—for most carriers, there are simply more profitable markets,

- Universal service funds—often these are not in place or are not effective in addressing this urban-rural gap, and

- Lack of electricity—in many rural localities there is simply the lack of power.

Fortunately this situation is beginning to change, with the following dynamics making this rural expansion increasingly practical.

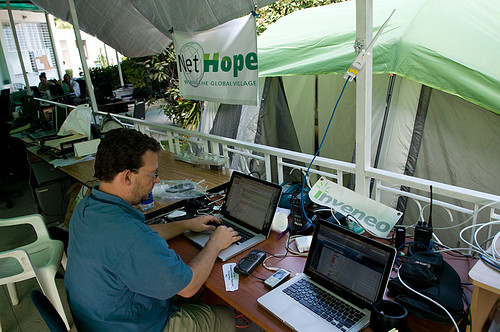

Smaller-Lower Cost Pico-Micro Solutions—most rural communities have an average population of less than 2,000, and equipment companies are just recently starting to deliver solutions that address this market

Lower Cost Backhaul Solutions—historically mobile backhauls have been proprietary—further adding to the delivery cost. The shift now is to a pure IP backhaul. And with this, edge switching is possible for keeping local calls local—a critical element when the backhaul is via satellite. IP backhaul also provides a single convergent solution that delivers both voice and broadband to the rural communities.

Photo Credit: VNL

Solar Powered Solutions—many of these small rural solutions are capable of being powered by solar, both at the tower-base station, as well as for the mobile handsets. This is an absolute requirement as the number of communities not connected to a national grid is very similar to those without mobile/broadband coverage.

MicroTelco Business Model—the emerging technical and business model needed to address the rural challenge is that of a massively parallel approach. This requires a technology that can be installed and supported by non-technical staff. It also requires an approach by the carrier that move primary support to the rural community–possibly through a local community operator under the license of a carrier.

While the industry is just now beginning to focus on this market, a number of firms are starting to deliver low cost rural mobile solutions. There is considerable variance in these solutions, but some are beginning to get the monthly average revenue per unit (monthly ARPU) required for sustainability of voice services, down to the $3-5/month range. The following reflect several:

VNL—VNL is a company from India that has introduced a WorldGSM product line and community business model

Altobridge—Altobridge is an Irish company with a unique set of technologies and business model

STM Group—The STM Group offers complete backhaul and local distribution through their SuperPico GSM products

Ubiquisys—Ubiquisys one of a growing number of Femtocell firms delivering rural low-cost rural solutions

Nokia Siemens Network—NSN’s Village Connection solutions deliver low Monthly ARPU solutions for rural settings

Alcatel-Lucent–Alcatel-Lucent has been making recent investments in their arena and are poised to introduce a new line of low-cost solutions suitable for rural areas within this new year (CY2011).

The above represent an exciting opportunity for ultimately eliminating the urban-rural divide. The GBI program is actively researching and engaging the above firms, along with others, to better position these within the overall context of USAID’s focus on addressing the rural gap.