The future use of the information and communication technologies (ICTs) such as e-vouchers in delivering subsidized fertilizer (or other inputs) to farmers in the current information age is blurred due to the very high cost involved in setting up such systems and the anticipated power/energy problems. This was one of the revelations made by experts from the International Fertilizer Development Center (IFDC) and the World Bank during the January 2012 USAID’s Agriculture Sector Council Seminar held in Washington DC.

Ian Gregory, a consultant from IFDC spoke on the subject “Voucher Schemes for Enhanced Fertilizer Use: Lessons Learned and Policy Implications” and David Rohrbach, a Senior Agricultural Economist at the World Bank shared his experiences from eastern and southern Africa remotely from Tanzania on the subject “Opportunities and Risks of Fertilizer Voucher Programs.”

The speakers argued that based on their earlier experiences, using ICT-based systems to facilitate fertilizer delivery through the subsidy programs can be very expensive. This includes the initial cost of establishing such a system as well as maintenance cost due to the absence of ICT infrastructure and low ICT human resource level in their respective areas of operation. Also anticipated is the lack of power or energy (electricity) in the communities that these inputs are distributed.

This revelation came in at the time when the World Bank had just launched an eSourcebook on ICTs in Agriculture with a comprehensive list of innovative practice summaries that demonstrate success and failure in interventions. Among them is the use of an electronic voucher system in Zambia, an initiative that was reported in 2010. The system is currently being piloted by the United Nations World Food Program (WFP), CARE International, and the local Conservation Farming Unit (CFU) with support from Mobile Transactions (a company specializing in low-cost payment and financial transaction services). The e-voucher system empowers smallholders to obtain subsidized inputs from private firms (giving the firms, in turn, an incentive to expand and improve their business).

Fertilizer subsidy programs

Giving the background to the fertilizer voucher schemes, Ian stated that while the traditional fertilizer subsidies were an integral policy tool of the Green Revolution in the 1960’s, excessive fiscal costs and risks, late delivery, rent-seeking, political economy and patronage, rationing, lack of equity and efficiency, and displacement of the private sector led to the demise of these subsidies in the 1980s. But the fertilizer subsidy programs have resurfaced in the last ten years as a results of high international fertilizer prices.

David from the World Bank Tanzania also identified some of the risks associated with the program as vouchers (or fertilizer) being distributed late; vouchers redeemed by agents distributing the fertilizer; counterfeiting vouchers (or fertilizer); vouchers redeemed for cash; price inflation: greater demand than fertilizer supply (top-up or subsidy grows); number of target recipients grows faster than population; and over-reporting of production.

Is there a need for e-vouchers?

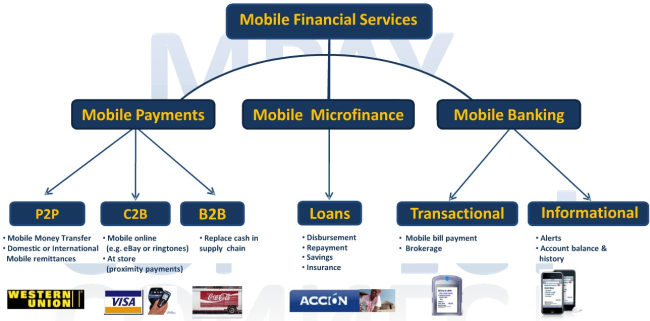

On the future direction of the fertilizer subsidy programs, David Rohrbach mentioned smart vouchers and ICT based systems as one of the possible reforms. Also possible is the effort to improve fertilizer use efficiency; find alternative strategies for strengthening competitive input markets; test alternative exit strategies; and explore the option of third party monitoring for improved management. These are areas that information and communication technologies could be strategically deployed for an efficient system.

According to the eSourcebook, the mobile transaction system in Zambia is enabling electronic monitoring of the e-voucher system, documenting which vouchers have been redeemed, where, and for which products, thereby improving the efficiency and effectiveness of the input subsidies. Also because farmers are registered with the system, they can be identified more effectively for specific training programs with input- and productivity-enhancing components. The e-voucher system also supports private agribusinesses by making them the direct source for inputs; as more private input dealers choose to participate, competition may increase.

With the success of the Zambia’s e-voucher pilot case, and the immense benefits that both farmers and the private sector providers can gain from such a system, I wonder why cost should still be an obstacle to its implementation in other countries. It may be true that an e-voucher system may not be easily accessible to these rural poor communities at this time, but the steadily decreasing costs of ICTs and the Internet infrastructure all point to a promising future. I believe this is a great opportunity for the private sector and the young entrepreneurs in these parts of the world to explore.

Cases of fertilizer subsidy programs

The two experts also compared fertilizer subsidy programs like the Sustaining Productive Livelihoods through Inputs for Assets (SPLIFA) of Malawi, Agricultural Inputs Support Program (AISP) also in Malawi, Ghana Fertilizer Support Program (FSP), Zimbabwe Agricultural Input Project (ZAIP), and National Agricultural Input Voucher Scheme (NAIVS) of Tanzania.

Some of the lessons learned include the fact that fertilizer subsidy programs do work for poverty reduction if targeted to vulnerable, potentially viable farmers and maintained for 3-5 years; they will also improve food security but at a huge cost and with leakage, crowding out, and mainly crop-specific; based on mixed evidence from 1980s, not sustainable; and they may work as a short-term fix for price spikes but distort markets, and at-source subsidy is a lower cost alternative.

Agrilinks is a new space for agriculture specialists and practitioners to access current information and resources on important agricultural and food security related topics and issues. The space leverages an array of experiences, resources, and expertise to encourage and promote knowledge flow among practitioners, USAID, partners, and other organizations specializing and working on current agricultural development issues. Visit Agrilinks for more information on this and future events.