The World Bank approved in June a $20 million credit to support Moldova’s Governance e-Transformation (GeT) project. According to Philippe Dongier, World Bank ICT sector manager, eTransformation is “about leadership commitment for institutional reform and for citizen-centric governance.”

The project is part of a Government initiative to address Moldova’s legacy of corruption and bureaucracy inherited during the Soviet Union era by improving and modernizing public sector governance and increasing citizen access to government services.

As part of an institutional reform, the Government established in August 2010 an e-Government Center charged to develop a “digital transformation policy, a government IT strategy, and an open data roadmap”. In April, Moldova became one of the first countries in the region to launch an open data portal.

“The initiative is aimed at opening government data for citizens and improving governance and service delivery,” says Stela Mocan, executive director of the e-Government Center.

Benefits of GeT

GeT has several intended benefits that include increased transparency. The Ministry of Finance recently released a spreadsheet of more than one million lines, detailing all public spending data from the past five years.

“Publishing information about public funds will increase transparency,” says Prime Minister Vlad Filat

GeT also intends to reduce the cost of public service delivery. Through “cloud computing” infrastructure—in which applications and data are accessible from multiple network devices—the Government also expects significant savings in public sector IT expenditure.

Promoting innovation in the civil society sector is another key feature of the project. The Bank’s Civil Society Fund in Moldova—which provides grants to nongovernmental and civil society organizations—is supporting the National Environment Center in the collection and mapping of information on pollution of water resources. Since 80% of Modova’s rural population use water from nitrate-polutated wells, this initiative aims to empower citizens with the necessary tools to hold the Government accountable on the environmental policy.

E-Government: a worldwide phenomen

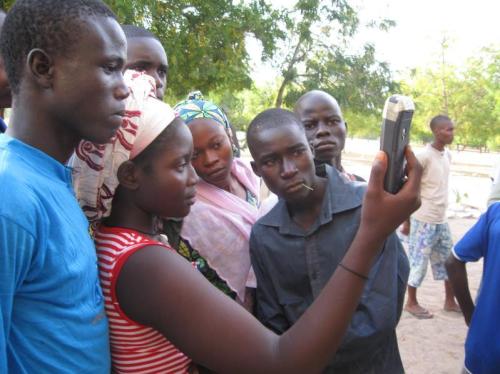

According to the Wolrd Bank, “e-Government” is the use by government agencies of information technologies—such as Internet, and mobile computing—that have the ability to transform relations with citizens, businesses, and other arms of government.

Moldova is not the only country using ICTs as part of an innovative approach to address corruption and strengthen democracy.

Chief Minister Prithviraj Chavan of the State of Maharashtra in Western India recently launched an e-Governance program that aims to tackle corruption by reducing personal interaction between the public and government officials and requiring government officials to use computers in their day-to-day operations. Limiting discretion and facilitating the process of tracking all transactions decrease the incidence of corruption.

To combat fraudulent activities during elections, the Electoral Commission of Kenya (ECK) upgraded its computer and communication network in 2002 to verify the eligibility of voters who had lost their voting cards or whose names were missing from the manual voter registers in the respective polling stations.

ICTs’ potential for addressing governance challenges is significant. Through increased transparency and accountability, governments can better serve their citizens. Implementing successful e-Government initiatives in developing countries is a challenging endeavor. However, sustained political commitment to institutional reform, citizen-centric policies, and financial backing create an environment where ICT applications can improve governance.