Google Creating a Map of Africa’s Broadband Cables

Google’s Sub-Saharan Africa office is funding a project by Steve Song to create a comprehensive map of all terrestrial broadband fibre-optic cables in Africa. Using crowdsourcing methods and contacts within the ICT4D space, Song is spearheading an effort to convince governments and telecoms that it is in their own interests to make public where they have laid terrestrial broadband cables. The project is named AfTerFibre (Africa’s Terrestrial Fibres).

AFterFibre, which started in June, is currently building its network of contacts, engaging governments and telecoms in conversation regarding the location of their cables. In an effort to be as public and open as possible, Song has organized a public google group to collect the information. As the group makes agreements and collects data, they will incrementally publish an updated map of Africa’s terrestrial cables, hopefully one about every two months. Then, next summer, they hope to publish the completed map.

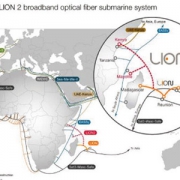

After creating the preeminent map of the undersea cables surrounding Africa last year, the next logical step was to make a map of Africa’s terrestrial fiber, explains Song. “The undersea map has inspired a lot fiber infrastructure construction. It gave people a sense that there is something to build to.”

The terrestrial cables map hopes to extend that vision to people in rural areas around Africa. Song imagines the mayor of a secondary or tertiary town in Botswana or Rwanda who sees the map and says, “we are only 100 km away from a terrestrial fiber. Why don’t we make our city the broadband hub in the region and transform our economy with this high speed fiber-optic connection?”

“We hope that the map is more than just a reference tool, but a sign of inspiration. When you see all the connectivity in the region, you can’t help but feel that something is about to happen,” Song said.

Presently, most operators in Africa are not publicly announcing the location of their cables, so people don’t know where they are. Song’s goal is to convince operators that they stand to benefit by releasing this information to the public, just as the operators arguably have after Song published the undersea cables map. Some operators have been skeptical about publishing the exact location of their cables, for fear of someone cutting them. Song assured the operators that the map will not be absolutely accurate, but simply accurate enough to spawn additional connectivity to previously unconnected areas. “So you won’t be able to locate the cables like you would locate a restaurant on your smart phone,” Song explains, but you will be able to locate the general area so that as a business or a local government you can make an educated estimate about how far you are to a connection.

The government of Kenya has been particularly resourceful in gathering the location their cables. The permanent secretary of the Ministry of ICT, Bitange Ndemo, committed his staff to gather and supply the information for the AfTerFibre project, effectively relieving Song from all of the logistical work. Ndemo’s commitment reflects Kenya’s recent move to make government data public and usable. Contrarily, in South Africa the process has been slower. Song contrasts the countries: “Everyone seems on the same page in Kenya. In universities, industries, and government there is a strong sense of ‘let’s transform Kenya and a strong sense of digital enterprise.’ Whereas in South Africa there is more finger pointing than creating a sense of common cause. In South Africa, we run the risk of losing information and the advantage that we started with.”