One Tablet Per Child: Walter Bender Discusses Future of OLPC

While listening to Walter Bender, founder and executive director of Sugar Labs, speak last week at USAID’s Mobiles for Education (mEducation) Monthly Seminar Series in Washington, DC, it was difficult to decide if he was more interested in discussing the One Laptop Per Child (OLPC)program’s new XO 3.0 tablet, or the educational philosophy that has spurred its development.

While listening to Walter Bender, founder and executive director of Sugar Labs, speak last week at USAID’s Mobiles for Education (mEducation) Monthly Seminar Series in Washington, DC, it was difficult to decide if he was more interested in discussing the One Laptop Per Child (OLPC)program’s new XO 3.0 tablet, or the educational philosophy that has spurred its development.The easily recognizable bright green and white rugged exterior is still present but now the 8-inch screen is protected by a green silicone cover. The child-friendly tablet was designed with the same consideration for durability, cost, and conservation of power that has made the OLPC program so well known, but now it features solar panels on the inside of the cover to power it in addition to the power adapter and hand-crank powered battery from the previous laptop.

Of course, the education-specific user interface of Sugar still remains and can be baffling to anyone not already familiar with it’s icons, a wide array of small visual representations of each activity that doesn’t resemble Microsoft’s or Apple’s familiar icons. But in Sugar’s design lies Mr. Bender’s philosophy and aim: a simplicity so intuitive that children can understand it as well as modify it and create new programs for their own use.

Of course, the education-specific user interface of Sugar still remains and can be baffling to anyone not already familiar with it’s icons, a wide array of small visual representations of each activity that doesn’t resemble Microsoft’s or Apple’s familiar icons. But in Sugar’s design lies Mr. Bender’s philosophy and aim: a simplicity so intuitive that children can understand it as well as modify it and create new programs for their own use.

As exciting as the introduction of the new tablet was for the small group of attendees at the seminar, Sugar was the focus of the discussion and one that Mr. Bender talked passionately about. Designed on OLPC’s principle of “Low floor, no ceiling”, it’s designed for inexperienced users, providing a platform, or low floor, on which to explore, create, and collaborate without any limits to its possibilities.

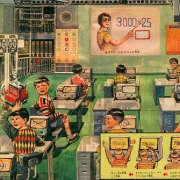

Exploration is key to Mr. Bender’s philosophy. Designing Sugar and the computers from a “constructivist” perspective, he referred to Swiss developmental psychologist, Jean Paiget, and his learning theory of “learning by doing” when discussing the intuitiveness of the system. “We want to raise a generation of independent thinkers and problem solvers, “ he said after displaying a picture of students taking apart and fixing one of OLPC’s laptops. “Every deployment has students who repair computers and they are designed so that students can fix them themselves.”

Already deployed in over 30 countries, the largest and most well known example is Uruguay with the largest saturation of one laptop per each of 395,000 children in primary school from grades 1-6. Now in its third year, Mr. Bender highlighted a few examples of how kids are becoming empowered through the technology and developing their own programs. Kids like 12 year old Augustine who created his own program called Simple Graph, one that creates just that. Mr. Bender said that innovations like this are examples of how students are becoming self-sufficient. “These are key indicators that something different is happening, something good.”

But this portfolio assessment, one that emphasizes qualitative over quantitative results and what Mr. Bender calls a powerful and primary assessment tool, is one of several points for criticism of the OLPC program. Others include not providing enough, or any, teacher training and support when introducing the laptops and not being able to meet the original goal price of $100 per laptop that was set when the program first started.

More recently, a new low-cost competitor, the Aakash tablet, has entered this developing market. The Android-based computer has gained a lot of attention since it was first developed by the Indian government as part of the country’s aim to connect 25,000 colleges and 400 universities in an e-learning program and made available at subsidized prices. In accordance with OLPC’s open source philosophy, chairman Nicholas Negroponte already offered full access to OLPC technology at no cost to the Indian team of developers.

Sharing ideas and new innovations is also one of Mr. Bender’s learning goals for the OLPC program: to have students learn through “doing, reflecting, and collaboration”. He believes that the new XO 3.0 tablet has a prominent role in the emerging market of mobile computers for education. Though what that role will be exactly in the coming years of new innovations and innovators, has yet to be seen.